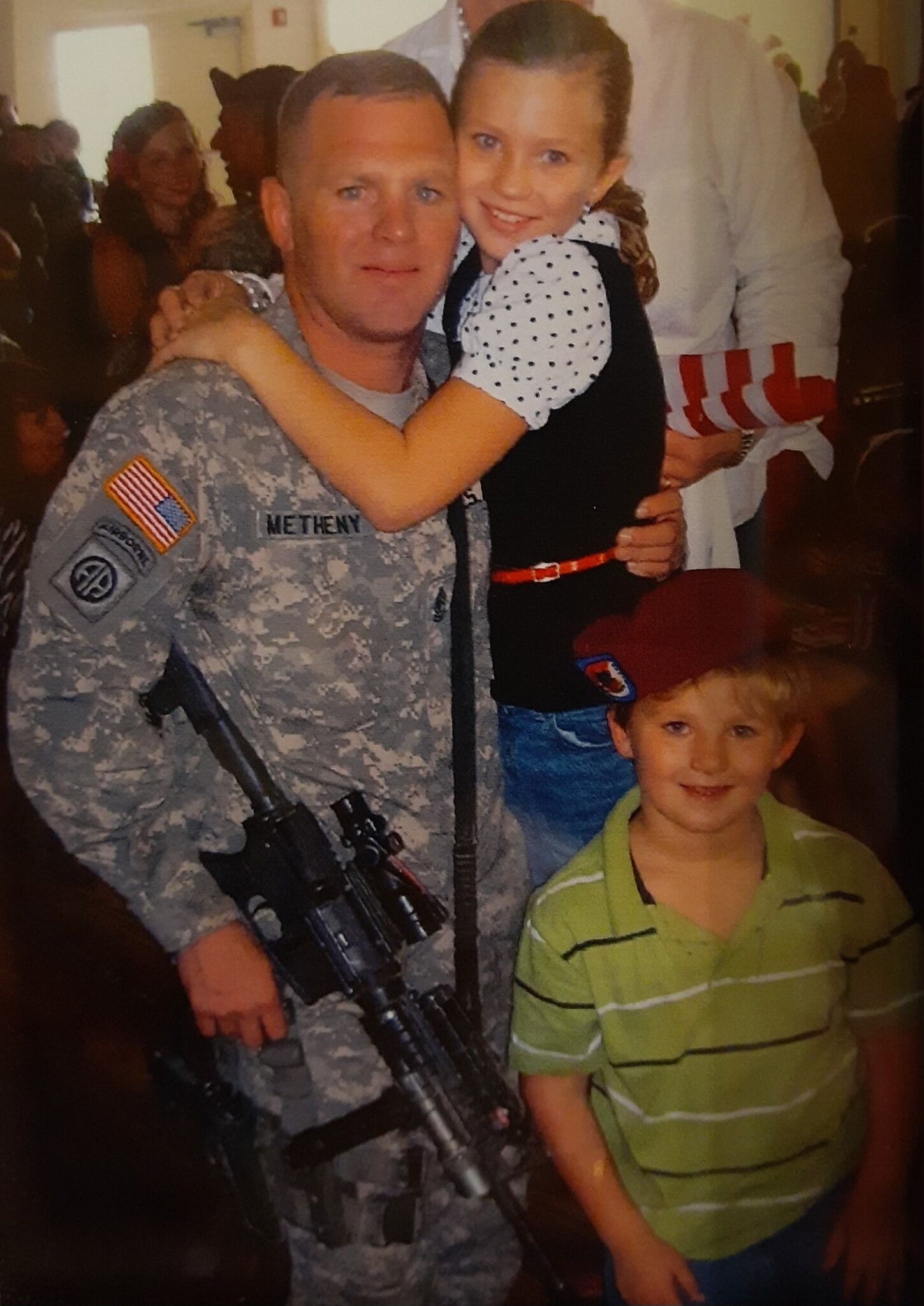

Tim Metheny

A Personal Mission

It’s late afternoon on a Thursday in March as Tim Metheny drives east in his Chevy Colorado toward Eglin Air Force Base to visit with some veteran friends. He’s carved out some time to mourn the loss of a soldier in between his travel for USA Cares Chapters’ events.

His humble nature and laid-back demeanor are not what most would expect from a retired Command Sergeant Major in the US Army. In fact, some would wonder why he isn’t spending his days on the Florida beaches near his home in Pensacola.

Tim explains that the mission he’s on doesn’t have time for sandy leisure.

“If I can prevent anyone from going through the pain and anguish and trials that my family had to go through, that’s my success,” Tim said.

As the Chapters Outreach Director, Tim plays an instrumental role in USA Cares’ mission to prevent veteran suicide. Apart from his commitment to serving other veterans, Tim’s dedication stems from his family’s own tragedy nearly ten years ago.

Duty Calls

“We called him Tough Guy,” Tim said of his only son, Zachary. “That was his nickname growing up because of his attitude. He was 100-percent boy.”

Tim smiled as he recalled a memory from when Zack was about 9 years old. It was Christmastime and Tim made Zack, along with his sister Madison, stand outside a Walmart to ring the bell for the Salvation Army. While Madison hid from embarrassment, Zack made a spur of the moment decision to start caroling in the parking lot.

“He was having a blast,” Tim said. “People were gathering so he told them, ‘Well, now you’re here, so donate.’”

Tim’s memories with his son aren’t as vast as other fathers. During his 33-year career in the Army, Tim often worked long days that only allowed for snippets of time with his children as they slept. While serving as a “Geronimo” in the 509th Infantry in the Fort Polk, Louisiana, Tim said he was gone for three weeks out of every month.

The lack of time together was hard for both Tim and his children. He recalled another story from his time as a drill sergeant at Fort Knox.

“I remember my daughter grabbing me at the door one morning, she was maybe 4, and she asked me why I liked privates (PVT) more than I loved her,” Tim said. “And I asked her what she meant by that. She said, ‘Well, you’re always with the privates. You’re never with us.’”

Then there were the deployments.

Tim estimates that he spent more than five years overseas on deployments to the Middle East while his kids were growing up. Before his retirement in 2022, he was the senior enlisted leader for U.S. Forces in Afghanistan and was deployed more than 30 months straight.

October 1, 2013

Tim woke up at his usual time that day and was grabbing a quick bite to eat when he noticed Zack up and dressed for the day. It wasn’t even 5:00 a.m.

“He’s up, and he’s dressed, and he looks great,” Tim said. “So, I asked him, ‘Dude, what are you doing up?’ And he said, ‘Just eating breakfast with you. It’s picture day at school and mom picked out the outfit.’”

When they got done eating, Tim encouraged Zack to go back upstairs and get some rest before it was time to go to school. Agreeing, Zack gave his dad a hug and told him he loved him before heading back upstairs.

Later, after Tim had been at work for a couple hours, he received a text from Madison around 8:30 a.m. She wanted to know if Tim had seen Zack because he hadn’t been on the bus that morning and wasn’t at school. Tim assumed Zack, now age 14, was probably skipping school.

After leaving work, Tim tried to look for Zack but couldn’t find him. Finally, Tim and his wife called the military police who began their own search for Zack.

Several hours later, Tim was sitting at his kitchen table waiting for word that the police had found Zack safe. Across from him sat a young police officer with headphones plugged into his walkie-talkie. Tim could hear a voice coming from one of the speakers.

“I heard, ‘We just found a body DOA at Clark,’” Tim said. “I asked him, I said, ‘What did he say?’ And he’s scrambling to get things closed back in saying, ‘Nothing. It’s nothing.’”

But it was too late. Tim knew.

Like he had with his father earlier that morning, Zack ate breakfast with his mom and then sister. Once everyone had left for the day, he took one of Tim’s pistols and walked the 200 meters behind the Metheny’s home to a terrace at a nearby school.

There, he watched the sunrise before taking his own life.

“I think I was numb because I was used to losing people in combat, but with this, I didn’t know what to do,” Tim said. “My wife was physically upset, screaming, literally almost pulling the hair out of the top of her head, and I didn’t know how to fix it.”

Confused and unable to process that his son was gone, Tim went to mow the lawn.

“I just needed to be doing something,” he said.

After a while, Tim tried to make his way over to where Zack’s body had been found, but he was stopped by police and told to return home. From where he was, Tim could still see the tarps hanging up around the terrace as the sanitation crew began cleaning the area.

“It causes immense guilt,” Tim said. “You know that saying, what’s your biggest regret? My biggest regret is saying no to going to play catch with him or I didn’t go to his football game because I had work or chose something else. You always wonder what you could have done better as a parent.”

The Picture

A couple of days before Zack’s death, the family sat around the living room as Madison opened her birthday presents. Tim decided to snap a photo of Zack while he sat watching.

“He’s sitting there and, man, he looks angry,” Tim said. “I actually hate seeing the picture.”

Two months after his death, the police released the letter Zack had written to his family. He addressed each member individually, sharing his love and appreciation for their role in his life. He ended it with:

“I’m watching the sunrise. This is a glorious life. I’m ready to meet God.”

Looking back, Tim wonders if Zack had suffered from CTE after years of playing full-contact football. Prior to his death, he had complained of headaches and was scheduled for a CT scan just days after his death. Without scientific evidence, though, what led to Zack’s suicide remains a bit of a mystery.

“It would be cool to have one more conversation with him to find out what happened,” Tim said.

Tim remembers Zack through little mementos. Every so often Tim dons one of Zack’s golf shirts or turns on his favorite music. Other times he pauses in front of a digital frame that shuffles through 30 photographs of Zack. Hard copies have been framed and hung up inside his grandfather’s home. Zack’s mother tends to his grave during the warmer months, and on his birthday, the family has a tradition of gathering for dinner.

“The grief never goes away,” Tim said. “Here we are, Month of the Military Child and Zack’s birthday is the 26th. That day, normally, just crushes me. You always wonder what would he have looked like, how he would’ve he have been. I think to myself, ‘Wouldn’t have been cool to see him go on his first date?’”

Instead, Tim is left with only memories of a son he described as playful, charismatic, and bright.

So, he continues on, devoting himself to helping save veterans and their families from the trauma he knows all too well.

“Does this make amends?” Tim said. “No, it doesn’t, but if we can just help one family stay together … We’ll never be satisfied, but once we help one, it’s on to the next, and then the next. We never stop.”